We were screaming down the freeway. Fifty miles above the speed limit. God, if you’re out there, now’s a good time. Devon Welsh—bulging delts, throbbing forearm veins, sweat dripping from his forehead—had just offered me a chance to change my life. Now, as the rearview mirror’s orange glow showed a city smoldering, a world turning to ash, I knew I, a humble music journalist, had no choice but to accept.

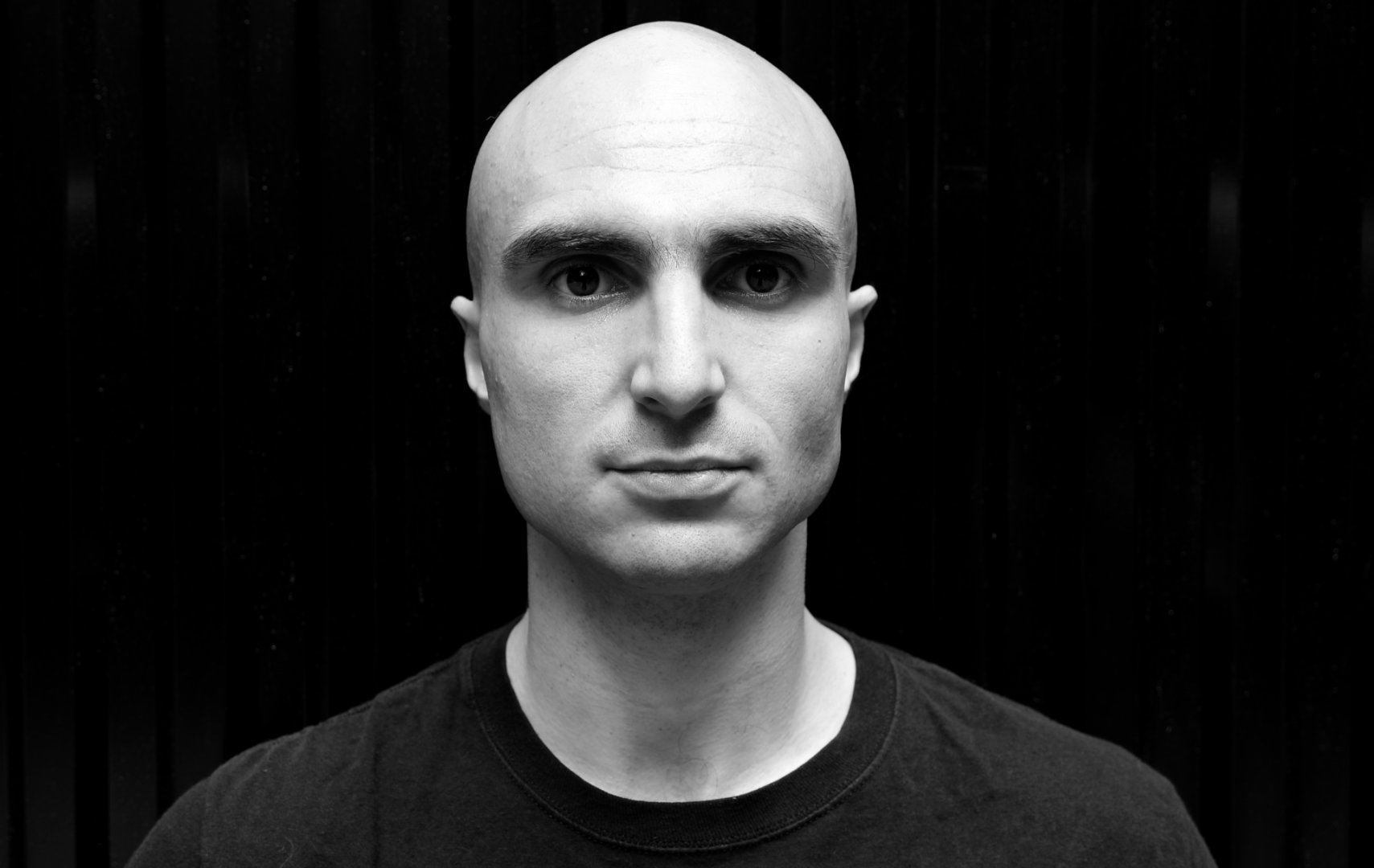

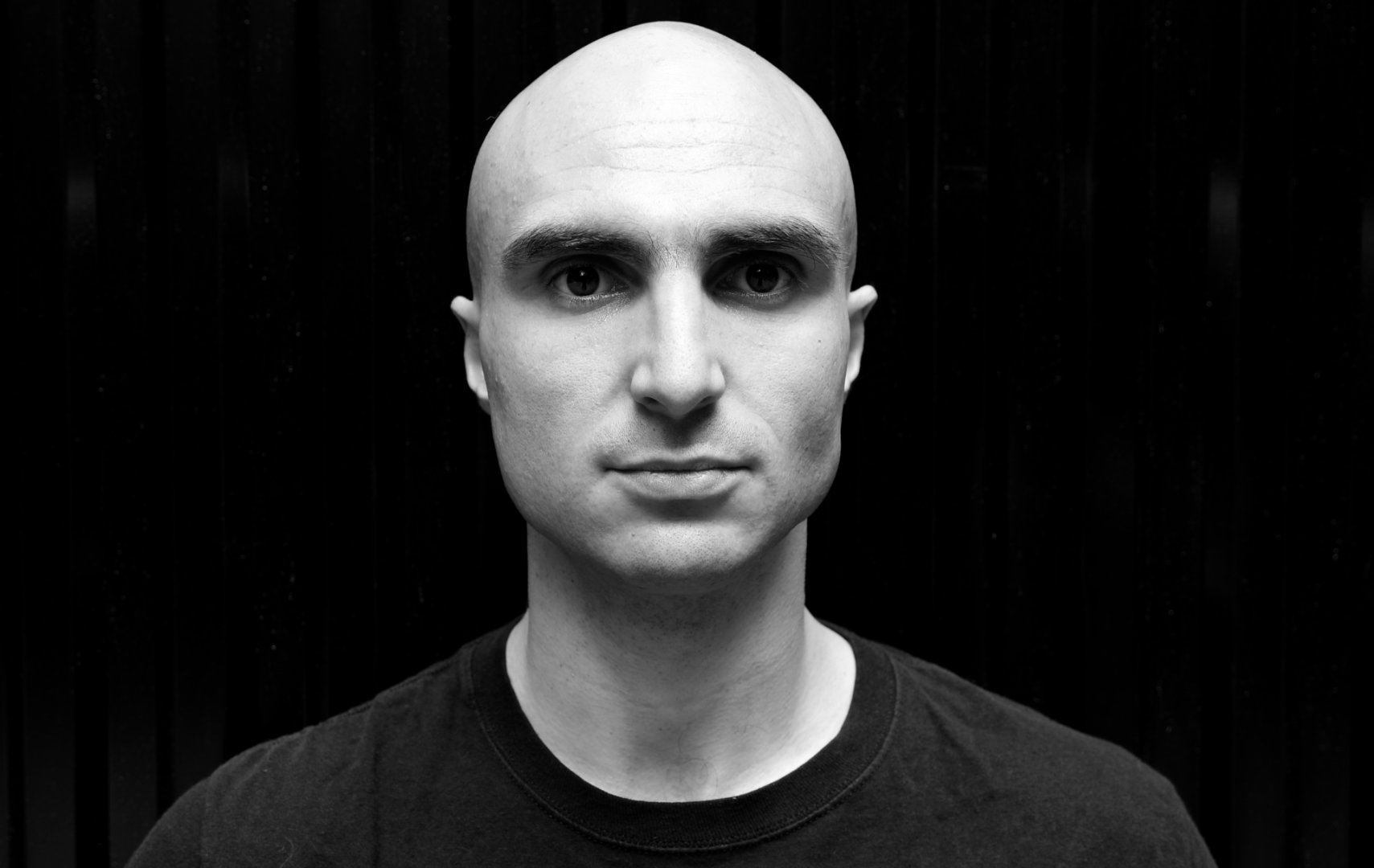

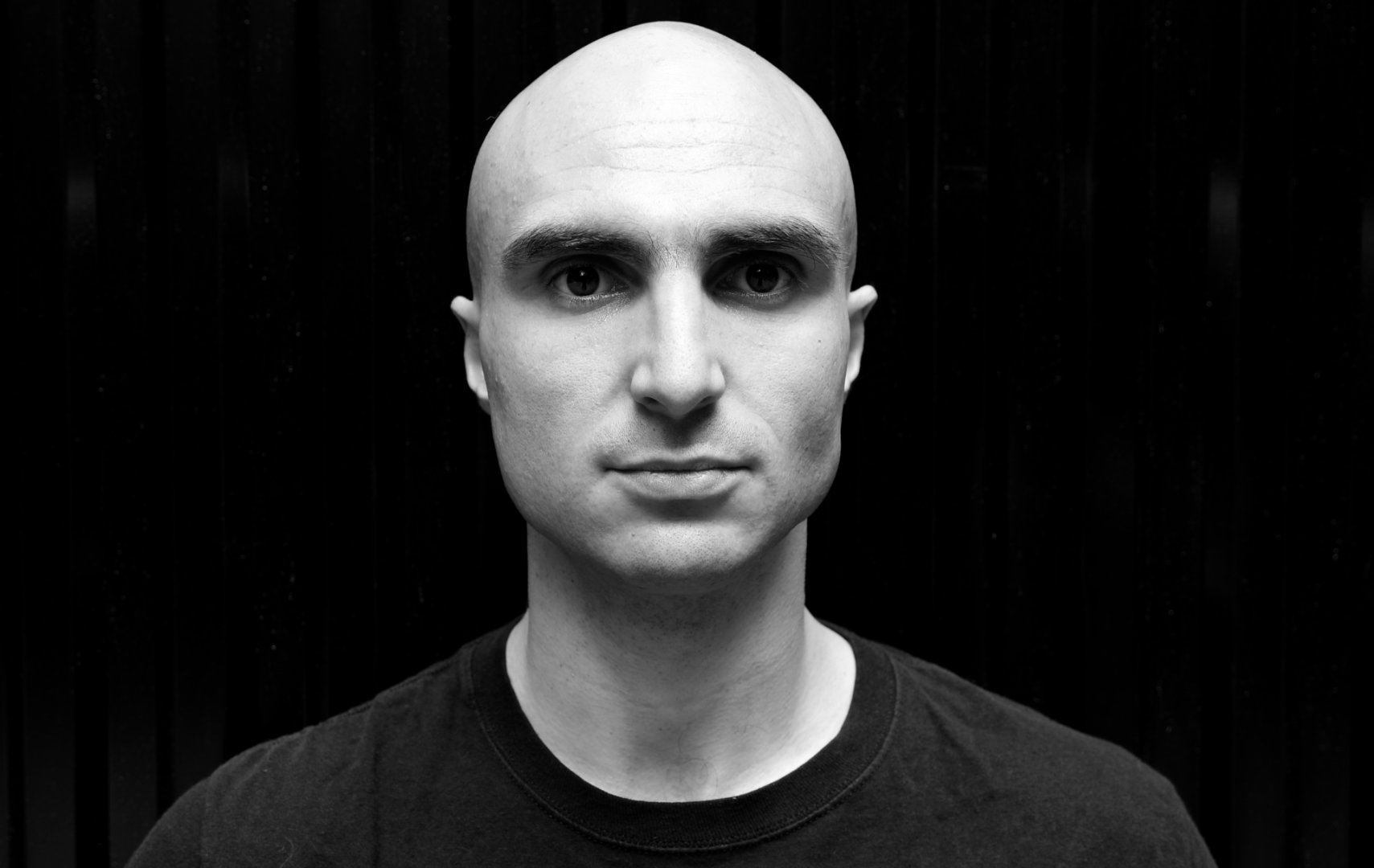

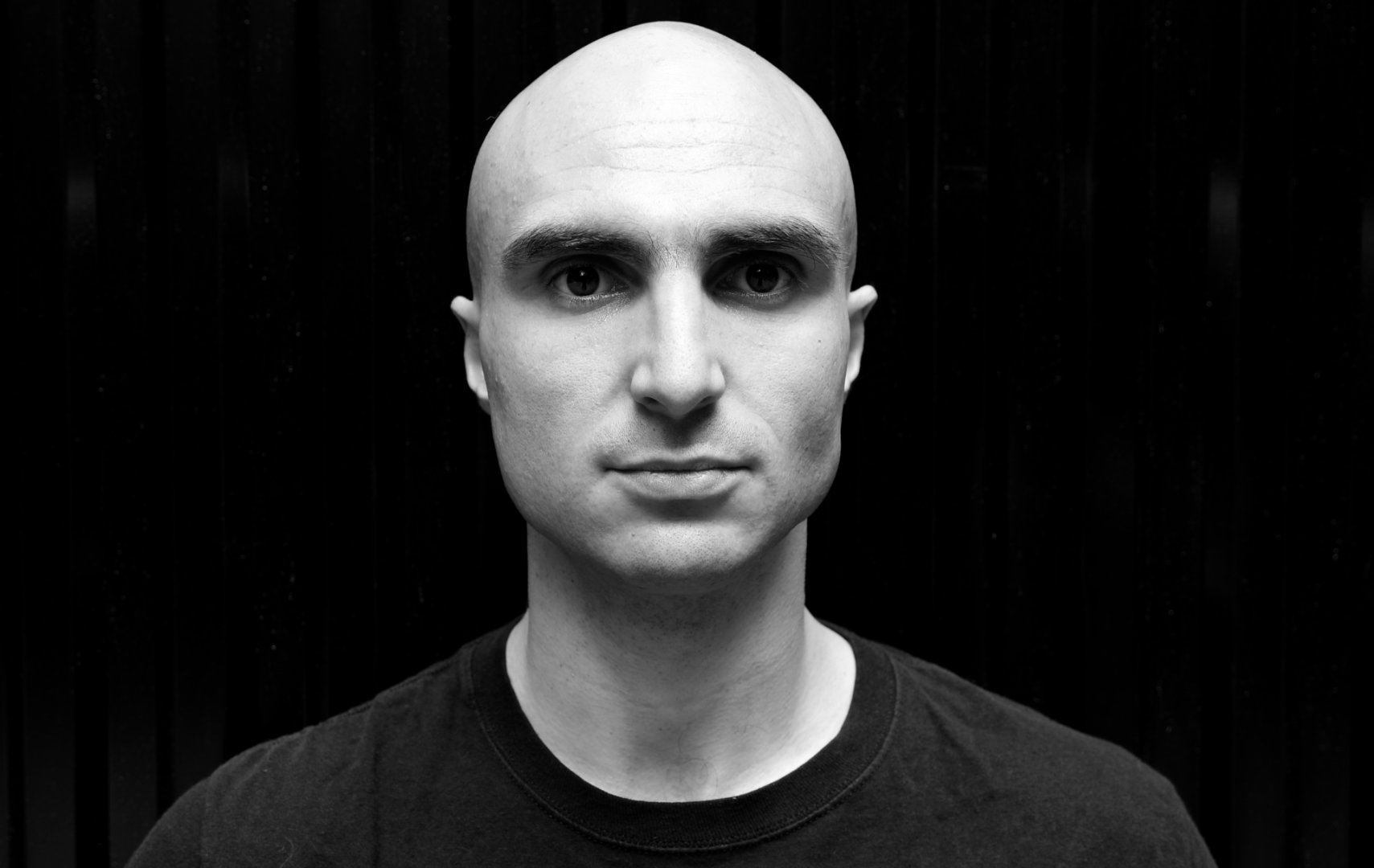

Explosions and sirens boomed and whined in the distance. We were listening to a copy of Welsh's new album, Come With Me If You Want To Live, as part of a feature I was writing on the record. Welsh's work had always foregrounded melodic accessibility and lyrics with an earned directness. As his artistic path diverged from the status quo, he grew more and more comfortable with iconoclasm and more comfortable inhabiting the spotlight. Against all odds, his career had gradually given him pop stardom—the kind that would have once accommodated perfume brands in your name, or let your hologram play festivals after you died. Welsh had become one of the most recognizable faces in America 2, with one of the most recognizable physiques: Rambo meets Arnold, with a dash of Houdini. But as his star rose, so did his infamy. Various freedoms had become privileges reserved for the elite. Welsh had a penchant for dissent, and now he had top billing on the country’s most-wanted list.

The new record was the apex, a kind of cri de guerre. The production was tight and spare, in the classic pop mold. The lyrics subtly excoriated societal systems, magnified close relationships, reckoned with the costs of fame, and generally said what people were thinking but afraid to say. Welsh had called the record a revolt against the state of music; because of his action-hero notoriety and prior history, it was generally understood that music stood in for America 2, or even the world at large. We were on the run because the government—our president, Harry Bongwater, was once described on national TV as “a grapefruit with glasses”—classified his album as a threat.

As Welsh's career ground on, the technologies and infrastructures that provided incentives for artists to develop had consolidated into a one-size-fits-all company called Architec, which had pivoted to technology from home decor wholesale. Industry insiders had long ago advised artists to optimize their recordings for their congruence with flash-in-the-pan technologies, and to present their music in live settings on grueling concert tours. Over time, a combination of inflation, supply chain shortages, rising costs of living, and a disappearing social safety net shut out more and more musicians from working, more and more audiences from purchasing their music, until the only artists left were extant stars like Welsh or benign voicebanks: Puno Tokën, Chinchin Tamakeri, Ashikoki the Great, Jokon U. Companies like Amazon and Spotify, now considered archaic, had pioneered two crucial cultural developments: they entrapped musicians and listeners within their data mining and sold it to them as freedom. Architec purchased the technology, refined it, and expanded the company’s scope. Meanwhile, they restricted the ability to listen to its technology, and limited the right to listen to users whom it classified as elite. Then—because they required every user, during registration, to provide proof of ID and undergo biometric scanning—they leased the data on a subscription basis to the government. As part of the deal, the government had codified Architec’s policies under law and agreed to use them as a baseline for further restrictions.

The media reported the news of the prohibition and the simultaneous rise of Architec with a breathless fervor, and consumers grew inured to the conditions: what choice did we have? How could we resist? And there were so few of us. Natural disasters, climate crisis, famine, war and disease had wiped out most of the world’s population—not to mention extreme sports accidents. Thanks to a clause Architec had inserted into the fine print, it owned the property of the deceased. The few who remained in the country clustered, curiously, in Chicago, which was relatively temperate (some years the thermostat hit ninety-five on Christmas), had relatively robust transportation access, and large bodies of water nearby in relatively good health. But, as a quick glance in the rearview would tell you, most of its older building stock was falling apart, bursting into flames, or being converted into exclusive skate parks for the few who remained.

We were headed towards Welsh's home in a rural area of what was once known as Wisconsin, which was just outside of Architec’s jurisdiction. The trick was to get there before Architec’s chief henchman, Chunk McGiff. If they caught us, they’d put us in solitary or worse. If we made it, we’d prepare to attempt a coup. Welsh made it sound simple.

As far as I could tell, the music didn’t overtly address this. Yes, the production had a quiet intensity, like an electric current. But the lyrics were just oblique enough to avoid easy classification. “Sister” and “Fooled Again” seemed like indictments of Architec and its defenders, but I wondered who their narrators and subjects really were. “Best Laid Plans” and “Twenty Seven,” I observed, contained poignant allusions to Welsh's earlier career (a charge Welsh nonetheless denied, moving his body from side to side as if to shake his head, a movement he struggled to execute, so big were his traps). And some songs could at best be described as aspirationally revolutionary: “That’s What We Needed,” say, or “Heaven Deserves You.” The former was fast, intent: “When you say, don’t be sad about it/I want to trust the world/but right now I just doubt it…today is overwhelming, tomorrow’s full of fear.” The latter had a more measured pace, but was no less direct: “Time makes everything new in the sense of change, but look what it’s done to you in the sense of decay/I want the change to be true.” The music was poppy but stark, built around dark, quick, synthetic beats, piercing instrumental melodies that often receded into the shadows of choruses, and the occasional double-tracked vocal or acoustic guitar strum. It barely passed the automated musical censors.

I found comfort in its austerity. This music was self-assured, and it wasn’t trying to be anything it hadn’t earned the right to be. In a past life, critics may have regarded a title like Come With Me If You Want To Live as heavy-handed. Here, with stakes as high as these, and so few critics left alive, it was fitting. Remember what music was for? Music could help you through a day you once thought unbearable. It could render your personal experience instantly relatable. You could put a record on and validate your quixotic wishes and your traumas. You could go to a big room with a sound system and a band, you could type words in a box and hit return, you could play or write or be a fan, and no matter your engagement, you could feel like you were part of something bigger than yourself. Music couldn’t save the world, but music could make you feel like your world was changing for the better. In times like these, Welsh's album was as good as any. He gave me his veinous, ultra-muscular hand, just as he had when we’d met for the interview earlier that afternoon: What are you waiting for? No time. Get in. Trust me.