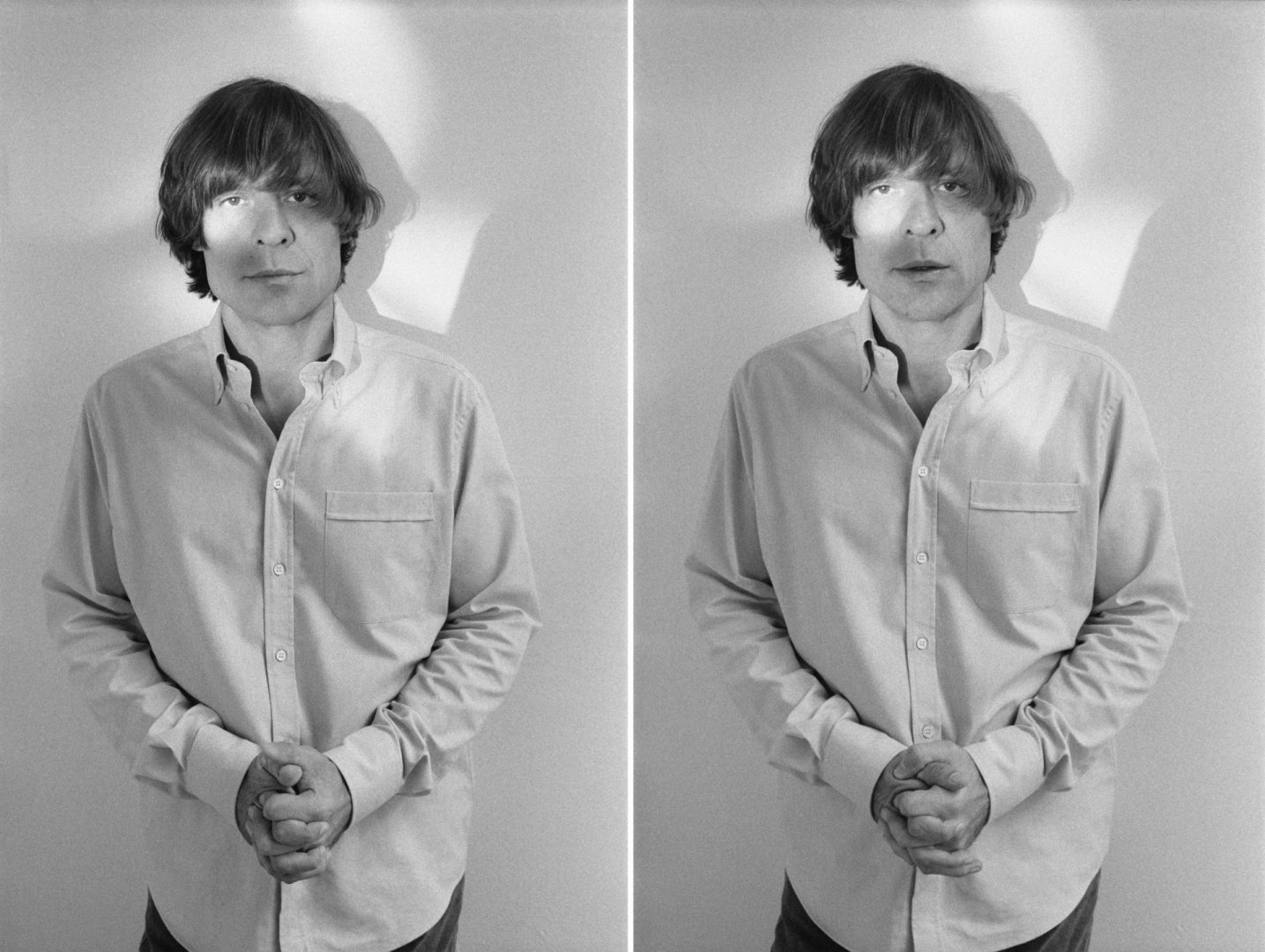

A man stands alone, his long brown bangs drenched in sweat. He paces the stage, runs in place, tears at his hair, strikes himself with his microphone. Propelling bass, mechanical drums, and heavenly synths spill from the speakers around him. When he opens his mouth to sing, his eyes widen dramatically and the tendons in his neck strain with intensity, revealing — in all its authenticity — the “hysterical body.” The man is John Maus, a 21st-century philosopher-musician who’s risen to mythic status in the last 20 years. His fierce belief in the emotional weight of sound, feeling deeply and thinking seriously, arrangements that sound as good at the club as they do at the symposium, bizzarro takes on popular music tropes, and legendary live shows have inspired legions of acolytes. His new album Later Than You Think, out September 26th via Young, is the clearest demonstration of this ethos to date.

Maus’s intensity is not a persona. The man behind the mythos is just as passionate as the one behind the mic — brilliant, fixated, earnest to a fault, and full of deep insight that gushes out whenever he speaks. In his work and his words, he’s constantly fighting the status quo: the Mickey Mouse Club, Coca-Cola, and all the institutions that reduce culture to its lowest common denominator. Amid all this, he’s managed to infuse his music with a dark sense of humor. From imagining sex with cars in 2006 to deadpanning “Your pets are gonna die” 11 years later, his satiric imagination has always been embedded in his seemingly stern aesthetic. Great artists, after all, must avoid the pitfalls of taking themselves too seriously.

Between four revelatory albums, Maus wrote a book-length dissertation on communication technologies as mechanisms of societal control and built an arsenal of analog synths in his basement. These achievements were the product of deep struggle. “Can’t write a word so you lock yourself up / So they say you’re losing your mind,” he sings on Later Than You Think. It’s a creative block he used to endure every time he picked up a pen, “wearied and burdened and ridden around like a donkey with a bit in [his] mouth by a trillion demons,” as he told Henry Wallis on an enlightening episode of the Forms podcast. Embroiled in spiritual battle — between the perfect and the good, but also between good and evil — he eventually found a path forward. But to understand Maus’s path to salvation, we must first know his road to rock bottom.

In late 2017, Maus released Screen Memories, his first album since 2011, and married the love of his life. 2018 saw him touring with a band for the first time, his brother Joe on bass. But things quickly crumbled. On tour in Europe the following year, Joe died suddenly of an undiagnosed heart condition. Then his uncle, who’d been like a second father to him, passed away, followed in 2019 by his aunt. The stress imperiled his marriage to the point of dissolution. “Let me through,” he repeats imploringly on Later Than You Think.

“I needed somebody or something to let me through the veil of tears,” he says now. “Let me through to the peace that Earth cannot give.” He turned to faith. Raised Catholic in rural Minnesota, he’d always been interested in spirituality from a philosophical perspective. After a quarter-century lapse, he returned to what he knew — attending church on Sundays, performing the acts of the liturgy, and “waiting for the glorious appearance of the Lord who will redeem the world.” Slowly, he began to pick up the pieces of his shattered life.

Maus was derailed again in 2021. On January 6, he went to Washington, D.C. to discuss composing the score to a new film by director Alex Moyer. He then accompanied Moyer to shoot footage of the protest at the Capitol. Long before things got out of control, they left. A video of Maus standing outside the Capitol circulated online, and justifiably angry people called for his cancellation. In response, he posted a 1937 encyclical titled Mit Brennender Sorge by Pope Pius XI against Nazi ideology, an act he saw as a pointed condemnation of the Right. Looking back, he realizes it wasn’t. “I should have been clearer that I’m absolutely against Trumpism,” he says. “It wasn’t as forthright a denunciation as it should have been.” Fans called him a fascist, and one festival even dropped him from its lineup. He understood. Ashamed at allowing himself to be adjacent to principles with which he so fundamentally disagreed, he retreated into seclusion.

Since then, he’s been rebuilding. In 2023, he started writing for the first time since the mid 2010s — a song per week for 20 weeks. Each day, he descended to his basement studio to work on new music. Forty tracks later, Later Than You Think was ready to be chiseled into a record. The result is a return to form, 16 songs that break new ground while harkening back to the many stages of his career — the bare-bones synth-punk anomalies of 2006 and 2007’s Songs and Love Is Real, the lush avant-pop cuts from 2011’s We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves, and, in a few cases, the symphonically ambitious endeavors of Screen Memories.

“Because we built it…We can watch it go up in flames,” Maus sings over live bass and a cybernetic drum beat at the start of the new album. “Because we killed him…We will watch it go up in flames.” While writing the song, Maus — who was born and raised outside Minneapolis — was reflecting on the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the protests that followed, particularly the powerful image of the Twin Cities being set ablaze in a fire of righteous revolt.

The songs on Later Than You Think are emotionally complex, alternately stoic and ecstatic. “Here’s your time for disappear,” he sings at one point, but this disappearance is ultimately a good thing. The death of self, of hubristic ego, brings us closer to the eternal. Elsewhere, on tracks like “Came & Got,” “Let Me Through,” and “Reconstruct Your Life,” he sings abstractly of his recent struggles, his tone ranging from desperation to resilience.

Religious themes and iconography surface throughout the album, shaping the emotional and aesthetic atmosphere. On lead single “I Hate Antichrist,” Maus repeats the titular phrase over and over above a pulsating drumbeat, a scowling bass line, and a high-register organ synth – its tone eerie and sacred – until the repetition becomes a mantra, driving the track toward a state of spiritual intensity and transcendent absorption. Halfway through, the song is interrupted by a sampled scream: “FBI! Open up!” “It’s about the cops coming in to get you,” he says, describing the track as “Cop Killer Part II.” (“Cop Killer,” a controversial cut from 2011’s Pitiless, is a metaphorical call to arms, a challenge to both fight the powers that be and kill the cop in our own heads. It’s a concept he wrote about the same year in “Theses on Punk Rock,” an essay he composed while in grad school. “Punk rock, like every truth, is anarchist,” he wrote, “[and] gives itself as a disordering of the Police.”)

Later Than You Think contains two Latin hymns, one rendered as a secular pop song, the other in Gregorian chant. He learned the latter technique while studying in an abbey of Benedictine monks in the Diocese of Tulsa, Oklahoma. “There's something radically antagonistic about that,” he says, referring to the way the monks eschew society to chant the hours seven times a day, from 4 a.m. to 1 a.m. He connects the act to the leftist concept of destituent power, as related in Bartleby the Scrivener’s simple phrase, “I would prefer not to.” The album title itself is a memento mori that Orthodox monks used to carve into skulls: “It's later than you think. Therefore hasten to do the work of God.”

Christian theology isn’t the only ideological system Maus explores on the album; good works can be secular too, he says. “Tous Les Gens Qui Sont Ici Sont D'ici,” he sings at one point, quoting a phrase from French philosopher Alain Badiou that translates to English as “All the people who are here are from here.” It’s a rallying cry for the acceptance of outsiders, a pointed rejection of xenophobia, delivered over motorik drums.

Later, on “Pick It Up,” an unofficial sequel to 2007’s “Do Your Best,” he sings of a down-on-his-luck city dweller who “sits in a fold,” waiting for a friend to show him a quantum of kindness. “We can never be reminded enough that we should reach out to lonely people,” Maus says. One way of doing this is through art: “People come up to me and tell me at shows that my music has helped them out a lot, and that's really humbling,” he says. “The truth is the truth,” he concludes, wherever it comes from.

Before ending the record serenely in Gregorian chant, Maus drops “Losing Your Mind,” a song about descending into madness. The track is split down the middle by a jarring noise sequence that he synthesized from scratch, a disruption he likens to Joseph Haydn’s “Surprise Symphony.” It’s not the only moment on the album for which he used pure data to create chaos. In the middle of “Disappears,” we’re shocked back to life by a disorienting phasing effect, created as a spectrum drawing. The image he sketched on his spectrograph was the sign of the cross.

To truly understand Later Than You Think — and Maus’s entire body of work — is to travel through time. Even at his poppiest, he’s incorporated elements of centuries-old music, fixating on the counterpoint of early-18th-century composers like Bach and Handel. Here, he goes back to the 10th century, to a time when Gregorian chant was the only form of music approved of by the Catholic Church. At the same time, he flashes forward to the ’60s and ’70s, when the first modular synthesizers emerged. This convergence of medieval harmony and 20th-century technology is most evident on “Theotokos,” where thumping drums and a barely audible bass underscore an ambient synth organ and a monophonic chant - a slow march through digital liturgy.

Later Than You Think contains multitudes — the lush and the bare, the sacred and the profane, minimalist discipline and maximalist indulgence, counterpoint and simple pop harmony. But at the core of the commotion, one thing is clear: John Maus’s music insists on the power of genuine emotion and radical sincerity. Engaging deeply with the crisis of modern life, he longs for truth and transcendence in an age of irony, alienation and political decay. His new project is a radical reawakening - powered by faith, acceptance, and an urgent belief that time is of the essence and this is the moment of truth.