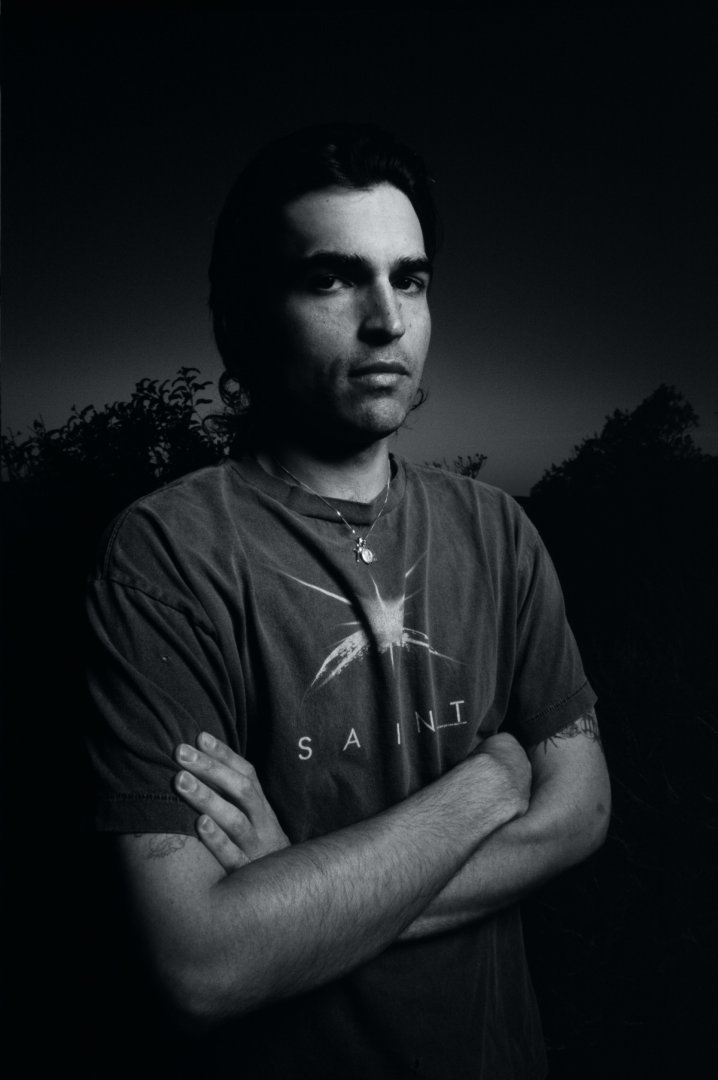

Vegyn's shape-shifting musical output as a solo artist has so far tended to fall into extremes. The 30-year-old producer – real name Joseph Thornalley – is partly known for his excess, working tirelessly with some of the world's biggest rap and R&B artists, and unleashing mixtapes of upwards of 70 tracks, letting light into his creative process by sharing reams of creative ideas and scraps from the cutting room floor. By contrast, his ebullient 2019 debut album Only Diamonds Cut Diamonds was an exercise in precision, or as Joe puts it, "trying to cut this thing into a super-sharp point".

But, as he worked towards his sophomore album, Joe found that he needed to break out of his old patterns. He made what he describes as "a couple sub par efforts" – records that will never see the light of day – before arriving at the ease, effortlessness, and song-driven approach that underpins his emotionally rich second LP, The Road To Hell Is Paved With Good Intentions. On this album, there are neither endlessly refined sonics, nor sprawling, open-ended ideas. Instead, there are sublimely crafted songs, each allowing for a dose of human imperfection, each wobbling on a tightrope between elation and an eerie melancholia.

In contrast to the technical prowess of his debut, Vegyn's second album emerged from a space of free-flowing experimentation. Often travelling as part of his work as a producer and label boss (of PLZ Make It Ruins), Joe wrote the new songs across studios, living rooms, and hotel rooms worldwide. "Some sessions were a deep dive into new – to me – analogue hardware, from the comfort of my home," he explains, "and others were back-to-basics, laptop-only sessions in a hotel room in south east Asia." He also wrote some songs at the piano, which he's been playing for around five years. "I still don't really know what a real chord is," he says, "but by just experimenting consistently, I've started to develop my own way of expressing what it is I’m looking for. I just try to look for the emotional resonance." Likewise, on this record he spent a lot of time playing around on the guitar, which he says makes him "feel like a baby". Production was less involved this time around, with his trademark flourishes and BPM changes taking a backseat to the melody and song structure. "I'm just trying to make interesting songs. There wasn't too much thought – feeling was the focus."

Still, there are plenty of the uncanny and darkly funny moments that make a Vegyn record recognisable. Most notably, there are the spoof radio station drops that happen periodically throughout the record, announcing eerie non-sequiturs like "hellbent on compromise" or "same old, same old". Each one gives the record a distinctly Vegyn feel. "I think the thing that's pertinent through all my work is a sort of happy melancholia," Joe reflects. "It's like, you've finally gotten to 'acceptance' in the stages of grief." In his music, while much of it has a bouncy, euphoric rush, Joe rejects toxic positivity: it's okay to be sad, he emphasises. "In the past, music was perhaps the only time I'd let my guard down and express myself."

The title, like all Vegyn titles, has a ring of ambiguity to it. Joe became intrigued by the common phrase when he started contemplating what it actually means: "Is it like, 'by doing the right thing, you actually make more problems'? Or is that 'the idea in your mind of doing good serves no purpose – you have to actually do it'?" Whatever it means, he muses, it's a phrase that captures the split between intentions and actions. For him, during the period of time in which he was writing these happy-melancholic songs, that theme resonated. The record, Joe says, reflects a kind of "stuck-ness. I felt so lost, and frustrated, and confused about what exactly it was that I was trying to do as an artist."

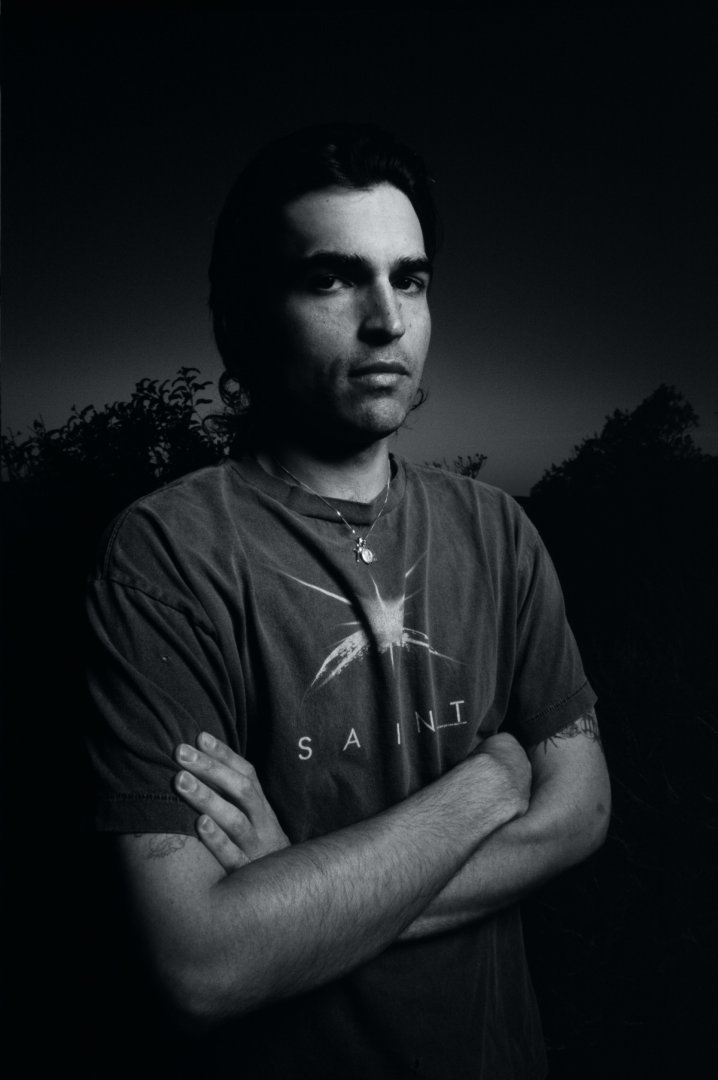

That lost sensibility comes through in the music, though it's not all bleak ("there's some fun to be had in disassociating," Joe grins). Take "Halo Flip", a restless, shuffling declaration of unconditional love, with echoes of grunge. "Even when you disappear, you know that you can come right back," sings Lauren Auder, over a rush of strings and cymbals. It's a warm hug of a song, looping its offer of solace and comfort – and yet, there's a ragged, tired edge to its optimism.

On its flipside is "In The Front", a elegiac track that features a monologue from London artist John Glacier over a bed of mournful, occasionally discordant strings. "The tears that I hide still filling up with steam/ Hot head, but they're never gonna see it," John intones, deadpan and steadfast about masking her real emotions. The song's outro draws a parallel between laughing and crying: two extremes that occupy different sides of the same coin. On The Road To Hell..., all emotions have this murky mercuriality, with happiness easily sliding into an underbelly of sadness, and moments of regret bouyed by hope.

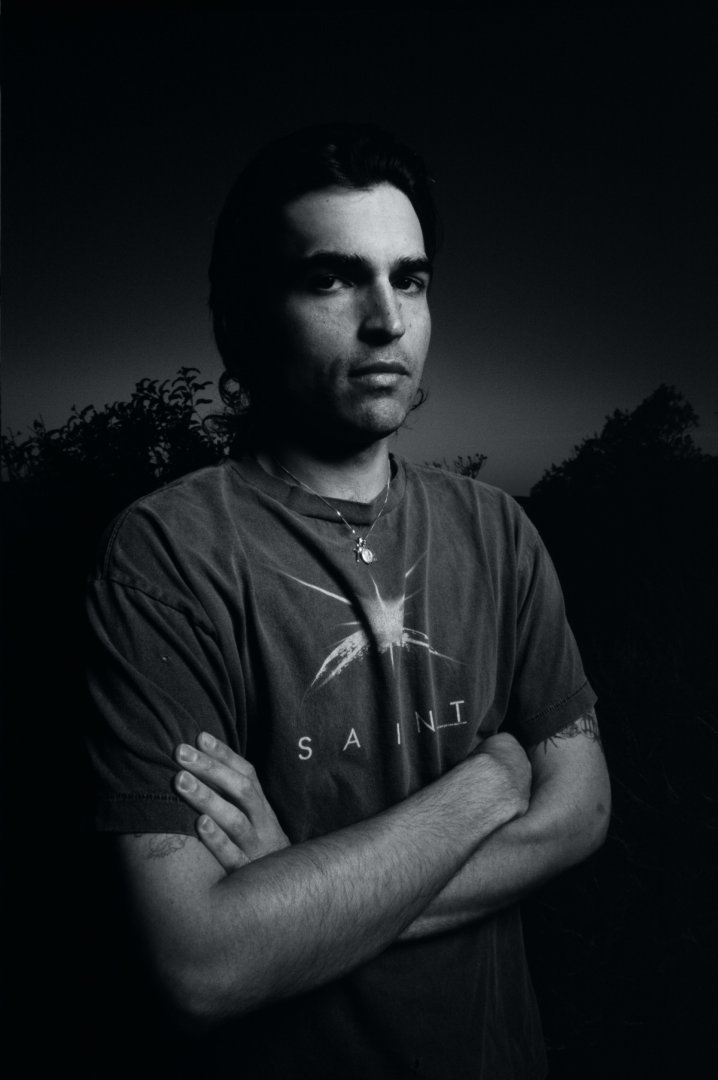

The record is peppered with the voices of experimental contemporaries, including the British singer-songwriter Ethan P. Flynn, avant-garde producer Loraine James, and grunge duo Double Virgo. "I like working with other people as it's the best way to let each other's strengths shine through," reflects Joe. "You get to sit back and think a little bit more objectively about what someone else might want, and that can greatly help to solidify what it is you want, too."

These collaborations, and rediscovering a sense of freedom and playfulness in music, helped Joe create his most cohesive body of work, and most accomplished songwriting, to date. "I used to think that important songs were the ones you toiled over for months and months, changing nothing," Joe says. "In reality, it's always the songs that took like, an hour from start to finish. The ones that are effortless." He points to the famous quote from David Lynch's book about transcendental meditation: that "ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you've got to go deeper". For Joe, this meant wading into previously unexplored reserves of emotional honesty, following his instincts, and learning to let go of striving for technical perfection. Next on his list is a live show, something that he's always been anxious about putting together in the past. "I'm trying to turn to new challenges," he explains. "What I've realised is that you have to put yourself in positions of difficulty, in order to grow."