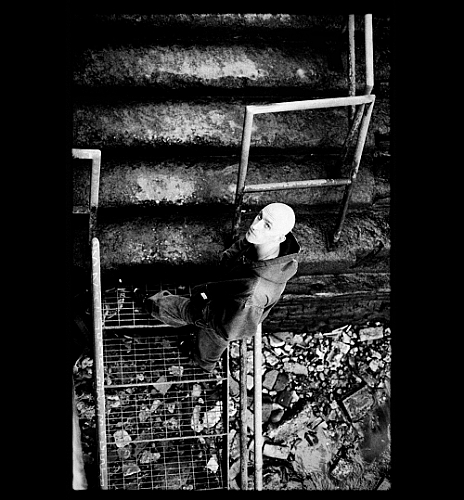

Mark William Lewis

Upcoming Shows

May 16, 2026

Brooklyn, NY

99 Scott

May 17, 2026

Brattleboro, VT

The Stone Church

May 19, 2026

Montreal, CAN

La Sala Rossa

May 20, 2026

Toronto, CAN

Longboat Hall

May 21, 2026

Pittsburgh, PA

Bottlerocket Social Hall

May 22, 2026

Columbus, OH

Rumba Cafe

May 23, 2026

Chicago, IL

WARM LOVE COOL DREAMS

News & Press

There are no articles available for this artist.